Icelandic Adventure

Caveat

We lived in Iceland from 1994 to 1996. Much has changed. The United States no longer maintains a military presence in Iceland, and the base seems to be full of Icelandic businesses. A lot of the businesses and clubs seem to have been replaced. Global warming is affecting Iceland, and at least one glacier has totally disappeared. The volcanoes on the Reykjanes peninsula have woken up from their centuries-long slumber, and no one knows what the future holds. As ever, Iceland remains the land of fire and ice.

The Beginning

After spending a second assignment at Cannon AFB, (making a total of 8 ½ years there,) Susanna and I were ready for a change. The opportunity arose for an assignment toKeflavik Naval Air Station, Iceland and we leapt at the chance. It was odd, but few people shared our enthusiasm. Other Air Force wives told her to make me go alone, and my own peer group, while understanding my desire to leave the high plains of New Mexico, were glad I was going instead of them.

I received my assignment on April 15th of 1994, and I was supposed to report in June. I couldn’t get permission for Susanna and I to travel together in such a short time, and I ended up travelling alone.

Part one was getting the car to Iceland. To do that I had to get it to a seaport. Since the charter flight to Iceland flew out of Philadelphia, I chose to ship my car from Bayonne, New Jersey. I took the opportunity to drive across the United States and experience what many people call “flyover country.” When I got to New Jersey and told someone I was dropping off my car at the port in Bayonne, someone asked, “Why go all that way? I can make a call and have it stolen right here.”

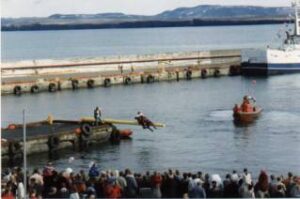

The flight from Philadelphia left at around midnight. I don’t remember what time I touched down in Iceland, but it was early Saturday morning, June 4th, 1994. The next day was the first Sunday in June, and was the Icelandic holiday called Seaman’s Day, although I didn’t know it then. I walked from the base to the town of Keflavik, just exploring and taking pictures to send home.

Despite extensive reading on Iceland, we were still a little worried about what the conditions would be. I was somewhat concerned that Susanna would change her mind, as all her friends were encouraging her to stay. As it turns out, they were all wrong.

As I made my way through Keflavik I noticed an Icelandic Coast Guard helicopter making repeated passes over the harbor, and as I approached the harbor I discovered a large crowd of people assembled to watch, and in some cases partake, of the oddest games. They had strongman contests; they had people racing from pier to pier using shovels to paddle the plastic tubs used for storing fish; and they had wet pillow fights on a telephone pole extended out over the water. The Coast Guard were wearing special orange dry suits designed to protect them from hypothermia, and helped ensure the losers were able to get out of the water. When I saw the winner take a celebratory dive from the pole into the frigid 35 degree water, I realized I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

Military Presence

Iceland gained its independence from Denmark during WWII. The British, understanding the strategic significance of Iceland in the North Atlantic, asked for permission to fortify the island. Despite the war and in spite of not having a military, Iceland refused. Being both arrogant and pragmatic, the English proceeded to occupy the island anyway, setting the stage for nearly six decades of friction between the two countries. When the United States replaced England as the defender of Island against the Hessian hordes, Icelanders were suitably grateful.

Eventually, the war was over. Once the Iron Curtain had divided Europe, Iceland was a choice bit of territory. If you look at a map of the North Atlantic you’ll notice that any submarine or ship leaving Russia must pass to one side or the other of Iceland. The country that controls Iceland controls the North Atlantic. As a member of NATO, Iceland entered the cold war on the side of democracy but, without a military, Iceland couldn’t defend itself. The United States committed its forces to the defense of Iceland and the Greenland/Iceland/UK gap. For many years the Navy tracked Soviet submarines through the use of its SOSUS warning nets and the P-3 Orion

I was assigned to the 57th Fighter Squadron just in time for it to be downsized. Its twelve F-15C fighters were sent to Tyndall AFB and I was suddenly out of a job. I quickly found a job as the Wing FOD Monitor and Flight Safety NCO, a position I held until I left Iceland. Part of my responsibilities included the Bird/Wildlife Aircraft Strike Hazard Program, (BASH,) a program that forced me to become a birder, at least for a while. While I was there General McPeak decided the 37th Fighter Wing designation along with it’s heritage should be transferred to Misawa AB, Japan. We became the 85th Wing, and then as part of the drawdown became the 85th Group.

Susanna was out of work for quite a while. The Navy civilian personnel system seemed to favor the wives of the officers over the wives of the enlisted, and the wives of the sailors over the wives of airmen. In time Susanna cracked the code and was hired as the director of Project Player, a Navy program to provide local activities for the single sailor. It was part of the Moral, Welfare, and Recreation division, (MWR,). Susanna soon was working with various Icelandic organizations to provide a wide variety of activities to the base population. Her capacity of program director and mine as her volunteer driver allowed us to explore Iceland.

Exploring Iceland

NAS Keflavik isn’t much to look at, so we didn’t. Instead we took every opportunity to leave the base and wander around the strange and wonderful countryside. To their credit, the Icelanders don’t charge the United States government to use the land it occupies. (They did force us to build them an international airport, though.) This is because no one wants the land. The Icelanders call it Satan’s Breath because it has the worst weather on the island. Because of the bad weather a large number of American servicemen and women never leave the base. That is a mistake. We soon discovered that even when the weather was terrible on the Reykjanes peninsula, the weather could be much nicer in Reykjavik and beautiful once we crossed the pass and descended into Hveragerdi, a town on the other side of the mountains.

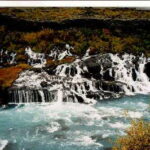

Iceland is a very beautiful country, but a harsh one. Jeremy Clarkson describes it as Scotland on steroids. It is a country painted in bold colors. The black lava hillsides are often capped with snow dripping down and fields of bright green moss climbing up, each in a vain attempt to claim the hillside for their own. Lava fields have their own stark beauty, but most people avoid them and miss their hidden treasures.

Vatnajokull is the largest glacier in Europe. Actually it is one of the last remaining ice caps from the last Ice Age. It rests on land too low to develop a glacier, but the ice cap is so thick it creates its own weather and thereby maintains itself. The yearly snowfall builds up until the pressure causes the ice to flow outward. What you see in this picture is one of the outlet glaciers.

While Iceland has a moist climate, the cool weather and the constant wind combine to make it hard on plants. They bloom quickly, but grow slowly. They stay low to the ground to avoid the wind and unless you get out of your car and walk you are unlikely to ever see them. (This doesn’t apply to the Blue Lupen, a non-native plant imported to stabilize the soil and fix nitrogen. It is taking over and driving out native plants. Fields of Blue Lupen are quite lovely, though.) Note the cairns, ancient piles of rock designed to guide people during bad weather. It’s bad luck to remove a rock, but good luck to add one—as long as it doesn’t fall off.

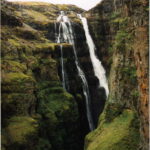

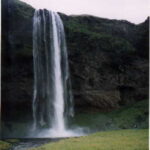

Iceland is a cool country, meaning it never gets really warm, but it never gets really cold either. The average winter temperature is colder in New York city. Unfortunately temperature doesn’t tell the whole story. Iceland is the windiest populated place on earth, and the wind chill can be quite severe. (This waterfall is being blown sideways.) Add the winter storms that come in three-day cycles and you have a recipe for a wet, miserable climate. If you let the weather stop you though, you’ll miss out on much of what Iceland has to offer. (Icelanders say the weather isn’t bad until you see whitecaps in the streets.)

The Reykjanes peninsula juts off the southwest coast of Iceland and into the Atlantic. Another way of looking at it is that the Reykjanes ridge comes ashore. The Reykjanes ridge is where the American and European tectonic plates are moving apart and new land is created to fill in the gap. There is a point on the Reykjanes peninsula where you actually see the different plates, and where you can stand with one foot in the new world and one in the old. The fault created by the plates moving apart is responsible for the high level of geological activity in Iceland. It creates good things like geothermal energy, and bad things like earthquakes and volcanoes. (This picture is of the cliffs at the very edge of the American plate. On the other side of the cliffs and across a shallow rift is the European plate.)

Life in Iceland

Iceland is unlike any other place. It is a sophisticated and highly literate country and has a remarkably high percentage of beautiful women. (Sorry Susanna, but I just had to fit that in.) The small town of Keflavik has around 12,000 people, (if memory serves,) yet has the latest fashions and cosmetics from Europe. The capital city of Reykjavik has nearly every type and style of restaurant imaginable. One notable exception was barbecue—I had to wait until I got back to the states for that. How many cities of fewer than 200,000 have their own Hard Rock Café? On the other hand, how often do you really want a $13.00 burger [1994 prices]? Reykjavik also has the ubiquitous fast food restaurants like McDonalds, (serving the only McMutton sandwich I’ve ever heard of; we used to call it the Big Maaaaaaaaac,) Pizza Hut, Domino’s Pizza, Subway, etc., but surely you don’t want to go to Iceland to pay outrageous prices for food you could get at home when you could eat a puffin? [I’m told McDonalds pulled out of Iceland.]

When Americans shop they go to the malls because that’s where the good shops are. [Once again, this was the case on 1994.] In Iceland the only advantage of the mall is that you are indoors. As long as you don’t mind walking a bit, you can find everything you want and need in the downtown area of Reykjavik. You may want to check out some of the side streets, though, since getting off the beaten path is how you find those special places you end up writing home about. If you want a preview of the shopping in Iceland go to the Iceland Review website. (While you are there, check out the online Iceland Review newspaper.)

Icelanders mostly speak English, although their native tongue is Icelandic, a language very similar to Old Norse. Some of the middle-aged and elderly adults might not be able to understand you, but most all of the shopkeepers and business professionals speak English. (The children all are instructed in four different languages. If I remember correctly, Icelandic, English, and Danish are required, and French or German are electives.) Most of the shops in Iceland take foreign money, but trying to figure out how much something actually costs is part of the fun of traveling. I’ve still got some of the money tucked away in a drawer. It’s not much good here, but it makes a fine memento.

One of the nicest things about Iceland is that it is safe. It’s small town America circa 1950s safe. Parents park their prams on the street while they go inside and shop. (Remember someone from one of the Scandinavian countries being arrested for doing that in New York?) American women are so used to being afraid they don’t even think about it, so freedom from fear is what they notice the most. Susanna was surprised to discover that she didn’t have to hug her purse and carry her keys in her hand as she walked to her car. Soon she thought nothing of leaving me with my friends at Kaffi Reykjavik while she wandered from club to club at 2:00 A.M. Icelanders are very honest, too. I once left an expensive camera under a table at a club and when I returned the bartender gave it back to me. You know the people are honest when even the drunks don’t steal.

The nightlife in Iceland is quite restrained during the week. As the Icelandic pop star Björk—rhymes with jerk, sorry but she said it first—as Björk pointed out, Icelanders don’t understand the idea of having a glass of wine with the dinner meal; they’d rather save it and drink it all at once. This makes Iceland a nation of binge drinkers. I spent many a Friday night with a group of friends at Kaffi Reykjavik, one of my favorite hangouts, and we had the entire place to ourselves until around 11:00 pm. Suddenly taxicabs began disgorging passengers at the bars and nightclubs and the bands began to play. Everyone arrives with a good buzz on and whatever drinking takes place in the bar is merely to keep the buzz going.

Before midnight the most popular clubs are full and have waiting lines. When people get to the front of the line they pretend not to have booze hidden inside their coats and the bouncers pretend not to have noticed these same people drinking while they were further back in line. Very civil, actually. At precisely 3:00 AM the bars all close and people are thrown out into the street where the party continues. Now those hidden flasks and bottles are quite handy. Around 5:00 AM people begin finding their way back home, but not by driving. The DWI limit is 0.05ppm, so one beer puts you over the limit. The penalties for DWI are very severe, so do what the Icelanders do and take a taxi.

Should you find yourself in Iceland on a weekend and are below the age where young girls think you’re old, check out the Astro. I’m 40 now, and well beyond that age, but when we were there it was quite a happening place. It was picked by a stateside television crew as part of its series on the most beautiful women in the world. The chosen costume of the stylish young women at the Astro leans more to short skirts than plunging necklines, so sitting near the stairs can be quite a treat.

Nordic custom is that the government is the sole source for alcohol. It is taxed quite heavily and is very expensive. I had a favorite little place I used to go where the beer was relatively inexpensive—$6.00 a glass. One thing’s for sure, the military doesn’t pay me enough to get drunk on $6.00 beers. As you might expect, home distilleries are quite the thing. People stay home and get drunk with their friends, then head out for a night on the town. I’ve been told it is illegal to run a home distillery, but usually people only get in trouble if they attempt to sell it and deny the government its tax revenues. Young people are quite bold about drinking homebrew, and the police pretend not to notice as long as the kids are drinking it out of soft drink bottles.

A peculiar thing about Iceland is that they all swim. The oceans and lakes are too cold to swim in, but they use geothermally heated water to provide for comfortable open-air swimming in any weather. The pools are usually ringed with hot pots, which are like Jacuzzis without the bubbles. Most of the pools have steam rooms and saunas, and many of them have tanning booths as well. At a few of the larger ones you can get a massage, a mud bath, or a facial. Many elderly people spend several hours a day in the hotpots, relaxing and swapping stories.

Swimming in Iceland exposes you to some peculiarities about Iceland. First, you are required to thoroughly shower before entering the pool. A sign on the wall points out those areas of the body requiring particular attention and a shower attendant watches to ensure you follow the rules. American men are used to gang showers, but American women often find this unnerving. Another peculiarity is that the locker rooms are not off-limits to young children of the opposite sex. Parents will bring their toddlers into the showers with them and showering in front of young girls is not something I’m used to. You can imagine how American women react when young boys are brought into the showers. I noticed some other oddities—Icelandic women wear modest one-piece bathing suits while the men wear Speedo’s. When I went to the Blue Lagoon I could tell the Americans from the Icelanders simply by the bathing suits. (I could tell the German women from the body hair, but that’s a story for another time.)

When we were in Reykjavik, we made it a point of seeing Villi Knudson’s Volcano Show. It was not a terribly sophisticated operation, but we liked Villi Knudson. He was married to an American, so he liked us, too. And he had a wealth of information on volcanism in Iceland. Unfortunately, I can no longer find any of his information online. He was an elderly man in 1994, so I suspect he has gone on to his reward.